Los Angeles is one of the most densely populated cities in the country. It also sits atop some of the largest oil fields in the country. That dynamic has long pitted residents of Los Angeles against the ever-encroaching oil industry — a third of Los Angeles residents live within a quarter-mile of an oil drilling site.

Now, a new lawsuit alleges that the city of Los Angeles has not been doing its part to protect residents from the detrimental environmental impacts associated with oil drilling.

According to the lawsuit, filed on Friday by a coalition of environmental and justice groups, the city of Los Angeles has a history of “rubber stamping” drilling applications, allowing oil operations to move through the permitting process without requiring the necessary environmental reviews dictated under California state law. Moreover, the lawsuit claims, the city’s lax permitting disproportionately impacts poor communities of color.

“Residents, especially in black and Latino areas, have been complaining about the impacts of oil drilling for years, and the city hasn’t done anything,” Maya Golden-Krasner, an attorney for the Center for Biological Diversity, which is a plaintiff in the suit, told ThinkProgress. “It’s a really stressful environment to live in.”

…drilling doesn’t belong in neighborhoods or parks. Those are just not appropriate places for drilling to happen

Los Angeles has always been an oil town — though it was officially “discovered” by Edward L. Doheny, Senior in 1892, the vast oil field that sits beneath Los Angeles was known to Native Americans and Spanish explorers for hundreds of years. But in recent years, spurred by technological advances like hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling, oil companies have been scrambling to pump even more from beneath the surface of the city. Applications for new or revitalized oil drilling operations have been on the rise, according to Golden-Krasner, which is how the Center for Biological Diversity, as well as several other justice and environmental groups, caught wind of the alleged malfeasance on the part of the city.

In most cases, according to Golden-Krasner, the groups found that the city of Los Angeles allows applications for drilling to go through without a formal environmental assessment under the California Environmental Quality Assessment (CEQA), a statute that requires state and local agencies to consider potential environmental impacts of any proposed projects. Instead of requiring an assessment, the city allows most companies to claim an exemption on their application, hastening the approval process — something that the lawsuit claims is in violation of CEQA.

Once a project is approved, the state can put certain conditions on the project, like requiring the operation to use a specific kind of drill, or placing restrictions on hours that the operation can run. It’s in these conditions that, according to the lawsuit, the city has been placing undue stress on poor communities of color, by requiring fewer conditions on projects in those neighborhoods than on similar projects in more affluent parts of town.

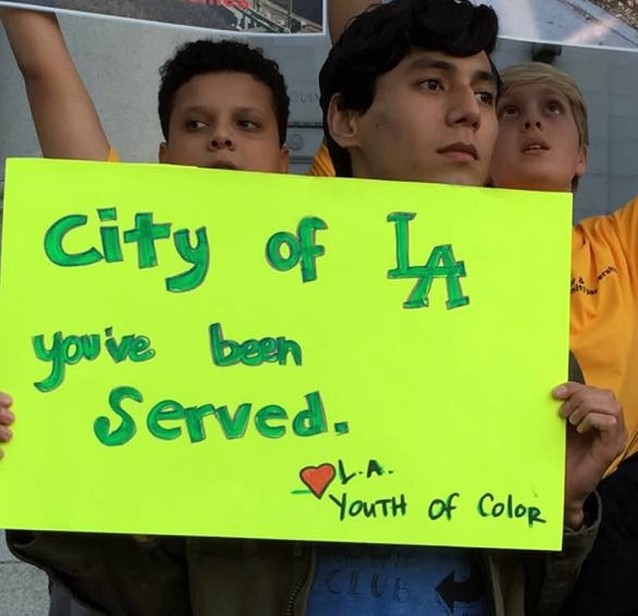

Youth demonstrate during a press conference Friday. CREDIT: Center for Biological Diversity

These discrepancies, according to Golden-Krasner, include things like requiring a drilling operation in a white area of town to use an electric drilling rig, which is cleaner and quieter than the diesel rigs allowed to operate in communities of color. According to the lawsuit, drilling operations in black and Latino communities operate under lax restrictions on hours — sometimes, drilling can go as late as 9:30 at night.

“People who live next to a drill site in Wilmington, in far south L.A., have described it as a living hell,” Golden-Krasner said. “They’ve reported neurological problems like dizziness, shaking, headaches, and nosebleeds. People have rashes, burning eyes, and respiratory problems, and trouble sleeping because of the noise.”

According to the suit, the city has granted three oil-drilling corporations approvals for at least 550 oil-extraction wells in Wilmington, a neighborhood that covers a little more than nine square miles.

Nearly 92 percent of the communities that live within a mile of oil and gas development throughout the state of California are communities of color

The disproportionate environmental burden felt by communities of color is not a new development, nor is it limited to the city of Los Angeles. According to a Natural Resources Defense Council report issued in October of 2014, nearly 92 percent of the communities that live within a mile of oil and gas development throughout the state of California are communities of color.

But communities are especially vulnerable in Los Angeles, Golden-Krasner explained, because of the city’s density. As new drilling operations seek to gain approval from the city, they’re competing for thinner and thinner tracts of uninhabited land. In one instance, the suit alleges, a portion of a community that had otherwise been set aside as a buffer zone between an oil project and a residential area has become increasingly populated, even as the drill continues to operate.

To have large-scale drilling operations located so close to neighborhoods, parks, and schools, Golden-Krasner added, is very unusual.

“It’s not just about whether [the city] complied with CEQA, per say,” Golden-Krasner said. “When the city really takes a hard look at the environmental risks and impacts, the city will realize that oil drilling doesn’t belong in neighborhoods or parks. Those are just not appropriate places for drilling to happen.”

The City of Los Angeles did not respond to ThinkProgress’ request for a comment.