At the end of this summer, Royal Dutch Shell heaved a seven-billion-dollar sigh of resignation and announced that it would stop exploration in the Chukchi Sea.

By then, the oil and gas giant had spent seven years — and that $7 billion — trying to get oil from under Alaska’s frigid waters, but after facing falling oil prices, heavy regulation, and broad outcry from environmentalists, the company put its plans on hold “for the foreseeable future.”

Environmentalists crowed that it was a “victory for everyone who hoped to avoid a catastrophic spill,” but what does Shell backing out really mean for the future of the Arctic?

What it does not mean is that oil exploration and extraction is going to stop altogether. That’s because the two or three main reasons Shell pulled out — dropping prices, regulation, and, maybe, environmental activism — are not permanent, and, more importantly, they don’t exist worldwide.

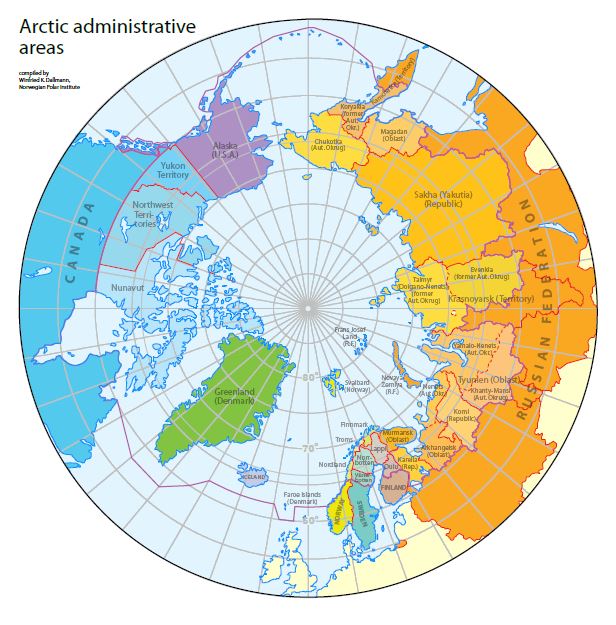

The United States controls only a small swath of the Arctic. Russia, Canada, Norway, Greenland, and Iceland also have Arctic coastline. Russia and Norway, like Alaska, are economically dependent on oil and gas, and the Arctic Ocean holds the potential for centuries’ worth of black gold.

Half of the Arctic coastline is Russian. Currently, countries have economic control for up to 350 miles into the Arctic Ocean, although that status is contended.

CREDIT: Arctic Council

In addition to holding huge oil reserves, the Arctic is one of the most ecologically fragile places in the world.

The region is considered ground zero for climate change — suffering diminished ice caps, rising sea level, and methane-leaking permafrost melts. Scientists have warned that extracting fossil fuels from the Arctic is incompatible with keeping global warming to below 2°C.

“In the Arctic region, an area that is becoming increasingly vulnerable because of climate change, to continue to go in there and exploit the region for fossil fuel resources… It’s absurd, and it’s dangerous for our planet,” Mary Sweeters, an Arctic campaigner with Greenpeace, told ThinkProgress. “The risk of an oil spill is so high, and the conditions in the Arctic are so extreme.”

The dangers are broad, ranging from global warming to threats to local wildlife. When Shell was allowed to conduct exploratory drilling this summer, the company had to keep the platforms 15 miles away from each other as part of a strategy to protect walruses and other wildlife. Seismic testing — a part of oil exploration — was also monitored, since it can disrupt the communication and hunting of whales in the area.

In other words, even under American regulations, possibly the strictest in the region, there are significant risks.

“Many experts have said we are not prepared for an oil spill in the Arctic,” Sweeters said. (In fact, in 2011, the U.S. Coast Guard’s top official told the Senate they had “nothing” prepared for an Arctic spill.)

Meanwhile, Russia is full steam ahead. Last year, the country announced it was shipping the world’s first tanker of oil from the Arctic Ocean.

Norway is drilling for offshore natural gas. Every day, Statoil’s Snow White field sends 735 million cubic feet of natural gas through a 90-mile pipeline to an island off northern Norway. Statoil has also been drilling exploratory oil wells in the Norwegian Arctic for 35 years. So far, they have not had much luck, but they keep going.

“The fact of the matter is, Norway is an energy-producing economy,” said Heather Conley, a senior vice president at the Center for Strategic and International Studies and an Arctic expert. “They are not going to stop.”

At the moment, developing the Arctic is less attractive than it has been for a long time. Extracting oil from under frigid waters, in a short season, with significant hazards, is not cheap, and — right now — oil is. The downturn in oil prices has hit Norway hard. Crude oil and natural gas made up 55 percent of the country’s exports last year, nearly $40 billion worth. Even though the volume of exported oil and gas rose, the value fell, contributing to a 10 percent decline in the country’s trade balance.

But oil prices fluctuate, and offshore drilling can be a game of patience.

“The Russian economy and the Norwegian economy are very energy dependent,” Conley told ThinkProgress. “As energy prices increase, the Arctic will become more interesting.”

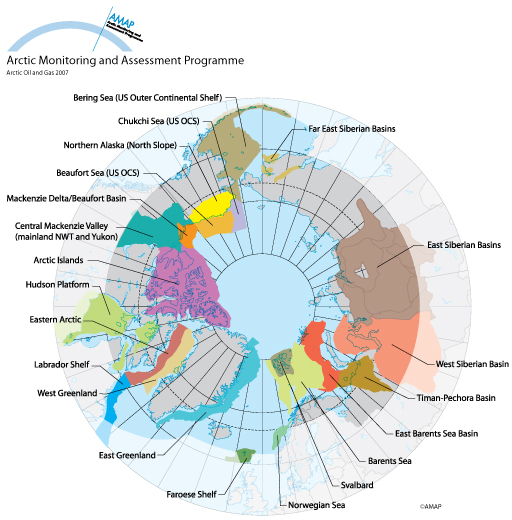

A major reason the issue of drilling in the Arctic isn’t going away is the simple scale of the reserves, estimated to be among the largest untapped reserves for oil and gas in the world.

“The anticipation of these reserves is so vast,” Conley said. “The reserves are thought to be really significant.”

CREDIT: Arctic Council

Russia’s president has made it clear that developing resources in the Arctic is a priority.

“The start of loading of the oil produced at Prirazlomnaya means that the entire project will exert a most encouraging influence on Russia’s presence on the energy markets and will stimulate the Russian economy in general and its energy sector in particular,” Russian President Vladimir Putin said when oil shipments began last year.

In some ways, Russia is moving ahead in an even tougher climate than other countries face. International sanctions have prevented Russia from obtaining the newest offshore drilling technology and diminish access to long-term financing. Arctic drilling projects can have 20- or even 30-year timelines, Conley said.

But on the other hand, Russia’s oil exploration is supported by the state, and is subject to significantly less regulation than U.S. or Norwegian efforts. This could mean that development from Russia is more dangerous than development from other countries. As Conley put it, there is a “greater risk-taking appetite” in Russia, while Western companies face greater regulation and the specter of liability if anything does go wrong.

So while the Obama Administration recently canceled lease sales for offshore Arctic exploration near the Bering Strait, those actions don’t necessarily protect the coast of Alaska from a potentially catastrophic oil spill. Russia’s current drilling is in the Pechora Sea, 38 miles northwest of Russia. But the country also has reserves in the Far East Siberian Basins. These reserves are not, strictly speaking, in the Arctic, but the current through the Bering Strait would carry any spilled oil directly to Alaska’s coastline.

A spill near Prirazlomnaya could be devastating for Norway and Russia’s fishing industry, as well.

“Any spill in the Arctic could potentially be catastrophic,” Conley said. “A lot would depend on where and when.” If, for instance, a drilling rig stayed beyond the short summer drilling window, it could easily get caught in conditions that would make stopping or cleaning a spill impossible. And, given Russia’s sometimes questionable relationship with the international community, it’s not even a certainty that the country would publicize an accident.

“You could really paint a perfect storm — literally and figuratively — for this,” Conley said.