The warmer it gets, the less productive a country’s economy will likely be — those are the results of a new economic and science study published yesterday in Nature. The study, conducted by researchers at Stanford and UC Berkeley, examined fifty years of historical data to see if there was a relationship between temperature and economic performance.

Looking at 166 countries — and taking out changes due to differences in countries (like geographic location or starting wealth) — the researchers analyzed whether a country’s economic performance increased or decreased as temperatures rose or fell.

They found that most countries have an economic sweet spot of 55°F — if a country tended to be cooler than 55°F, its economic performance tended to increase as it warmed towards 55°F. Once countries cross that threshold, however, their economic performance tended to decrease. The researchers found an especially strong negative correlation between a country’s economic performance and the temperature the warmer it gets — a country that begins with warmer temperatures, in other words, suffers a greater drop in economic performance per 1 degree of warming than a country that begins cooler.

“The data tell us that there are particular temperatures where we humans are really good at producing stuff,” Marshall Burke, professor of Earth system science at Stanford’s School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences, said in a press release. “In countries that are normally quite cold — mostly wealthy northern countries — higher temperatures are associated with faster economic growth, but only to a point. After that point, growth declines rapidly.”

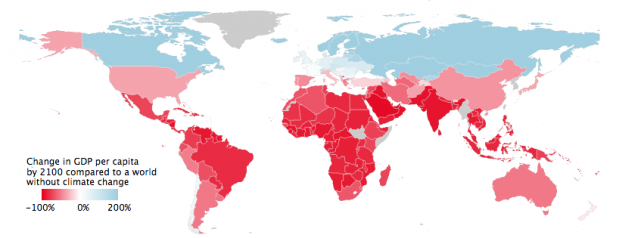

Perhaps more concerning, however, is what could happen in a world where climate change is allowed to continue unmitigated. Under that scenario, the researchers found, 77 percent of countries in the world would see a drop in per capita incomes relative to current levels, with global incomes falling 23 percent by 2100.

Change in GDP per capita by 2100 compared to a world without climate change.

CREDIT: Burke, Hsiang, & Miguel (Nature, 2015)

And that decline in economic performance holds true for both rich and poor countries, something that runs counter to the idea that rich countries can simply pay for technology to adapt and avoid the worst consequences of climate change.

“The data definitely don’t provide strong evidence that rich countries are immune from the effects of hot temperatures,” Solomon Hsiang, the Chancellor’s Associate Professor of Public Policy at UC Berkeley, said in a press release. “Many rich countries just happen to have cooler average temperatures to start with, meaning that future warming will overall be less harmful than in poorer, hotter countries.”

But, at least in the short term, global warming will likely exacerbate existing global inequalities, with the richest 20 percent experiencing slight gains as the world warms, according to the study. The poorest 40 percent of countries, meanwhile, will likely see a 75 percent reduction in average income in 2100.

As the researchers point out, correlation does not equal causation — Nigeria is poorer than Norway, they explain, but it would be flawed to say that Nigeria is poorer because it is warmer. But they argue that because temperature fluctuations from year to year are random, they can see how a particular country performs under cool and warm situations — effectively giving them a “control” with which to compare economic performance.

“If we see over and over that a country has lower economic production right when it also becomes hotter, then we can conclude that these environmental temperatures are likely causing these changes in economic performance,” the researchers wrote in a supplemental explanation.

Wesleyan University environmental economist Gary Yohe told the Associated Press that the study as significant and thorough, adding that it used “the most modern socio-economic scenarios.”

The study looks at a future where nothing is done to mitigate climate change, however, which is an increasingly unrealistic outcome as nations prepare to negotiate an international climate deal during the upcoming U.N. climate talks. In advance of the Paris conference, Burke hopes that delegates will enter the talks with a realistic idea of what’s at stake if the world adopts a business-as-usual approach to carbon emissions.

“Our research is important for COP21 because it suggests that these economic damages could be much larger than current estimates indicate,” Burke said in a press release. “The benefits of action on mitigation are much greater than we thought, because the costs of inaction are much greater than we thought.”